Of them, 13 have been caused by rip currents. Of those, six have occurred along the North Carolina coast — the most recent on May 25 at Southern Shores, according to a news release from police.

Approximately 100 people die from drowning in rip currents each year, the U.S. Lifesaving Association said.

There already have been hundreds of rescues along the country’s beaches.

And it’s not even officially summer yet.

“They’ve been hit pretty hard down there,” said Tom Gill of Virginia Beach Lifesaving Services. “We were lucky this weekend with low tide being early and late when fewer people were in the water.”

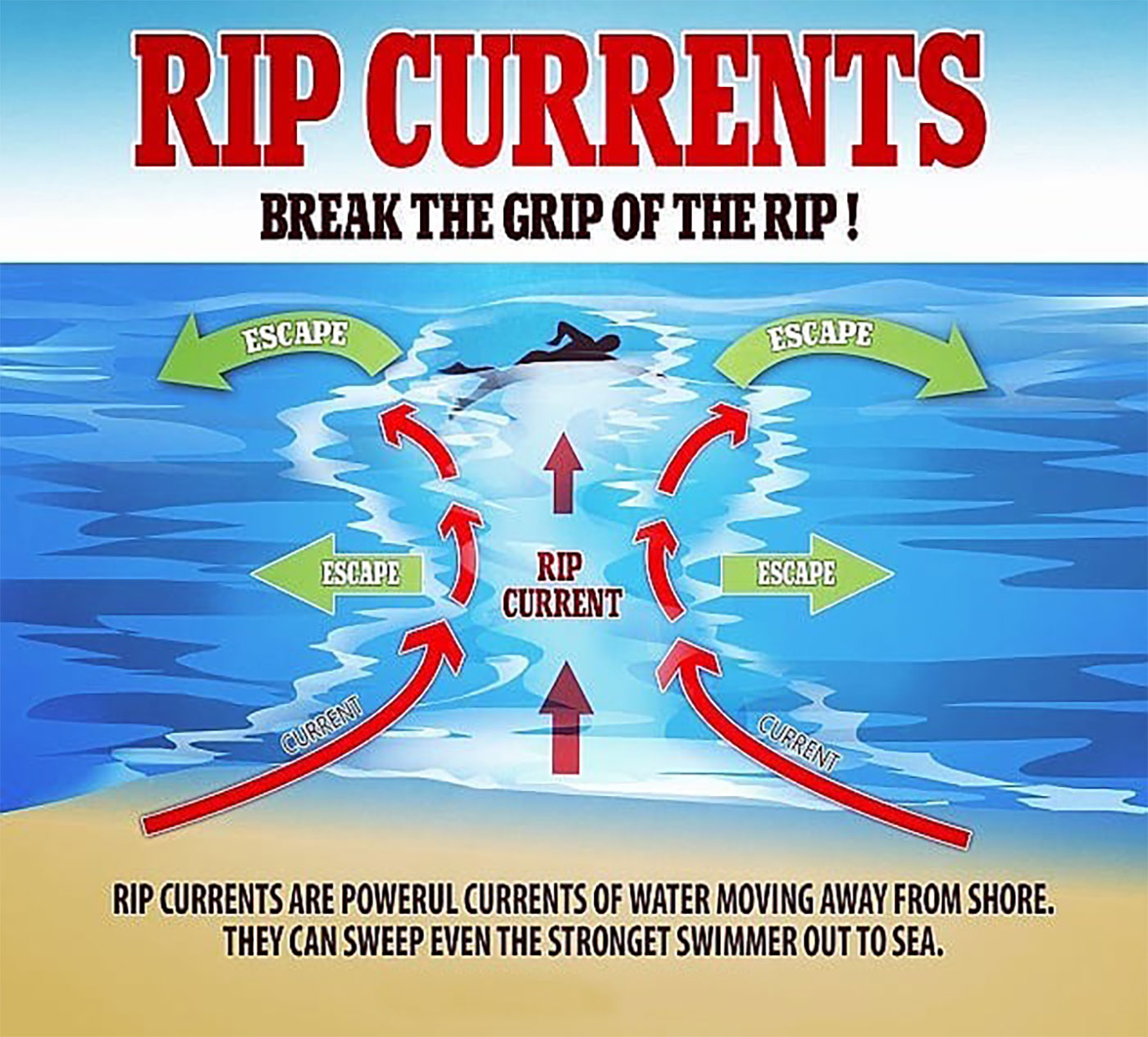

People in the area of the rip can be carried out past the sandbar before the current starts to subside. Some rips can go for several hundred yards. Deaths typically happen when people panic and try to swim against the current, tiring themselves to exhaustion quickly. Most are poor swimmers or those with no swimming skills at all.

“Rips won’t pull you under water, but people can go under as quickly as 30 seconds when they get tired,” said Gill, who also is the spokesman for the USLA.

Gill advises swimmers caught in a rip to simply float or tread water as the current pulls them out. Where the current isn’t as strong, start swimming parallel to shore until you’re out of the rip, then swim to shore. If you need help, start waving and yelling toward the beach.

“Our folks are really good at keeping an eye on the situation in the water,” he said. “Especially when their station is near where a rip has formed.”

The problem on the Outer Banks, he said, is a lack of lifeguard stations. The Cape Hatteras National Seashore that spans nearly 70 miles recently added a lifeguard stand on Frisco Beach, joining stands at Coquina Beach south of Nags Head, Hatteras Light and Ocracoke.

“There’s no way we could provide lifeguards on all of the beach,” said David Hallac, superintendent of national parks in eastern North Carolina. “So we’re providing them with safer places to swim where there are guards on duty.

“And we really focus on education.”

Hallac said he and his staff gave nearly 2,500 presentations about the national seashore to more than 76,000 last year, and part of each dealt with water safety. He said there are 200 signs warning visitors of dangerous currents and, in partnership with Dare County, visitors can get alerts on higher rip current and related risks.

“It’s important that people learn to recognize rips and know how to get out of them,” Hallac said.

There have been 20 drownings at the national seashore in the last three years. The stretch of beach is very susceptible to rips because of stronger wave action, deeper water closer to the shore and because it is more south-facing than Virginia Beach.

Gill said there were two drownings along Virginia Beach last year, both where there was no lifeguard stand or after the lifeguard season had passed. Hallac said most of North Carolina’s drownings have occurred where there was no lifeguard or out of season.

A U.S. Lifesaving Association study showed that swimmers stand a one in 18 million chance of drowning when swimming near a lifeguard. The odds are much less favorable when swimming in unguarded waters. The study showed that there were 131 drownings in unguarded waters last year, compared to just 17 where there were lifeguards.

“Swim near a stand, wear a life jacket if you aren’t a good swimmer, learn how to spot a rip area,” Gill said.

___

Information from: The Virginian-Pilot, http://pilotonline.com